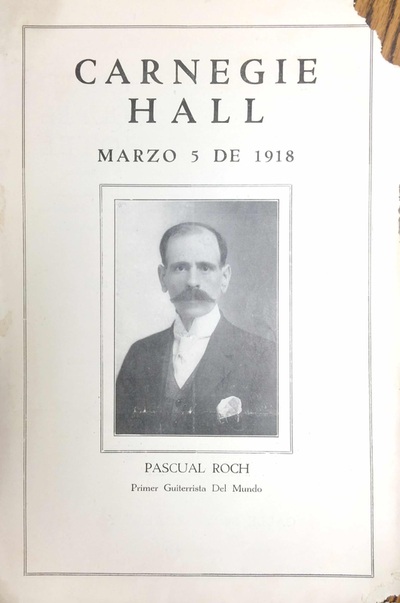

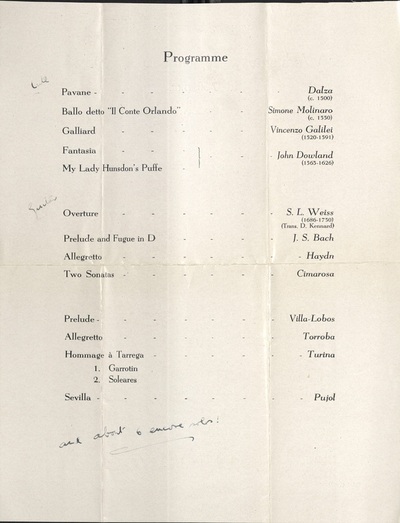

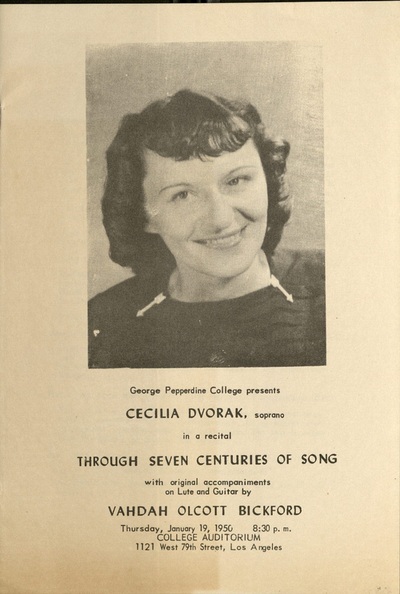

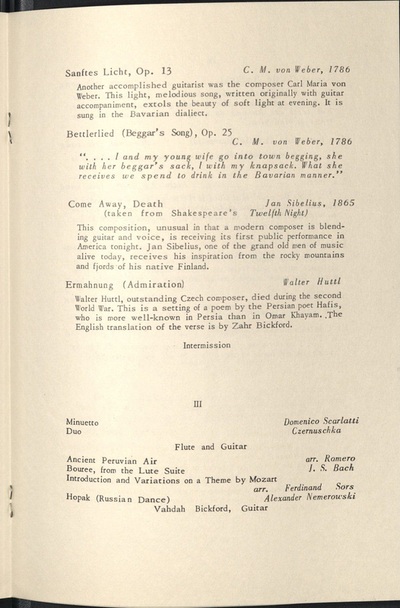

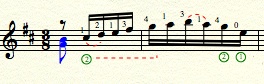

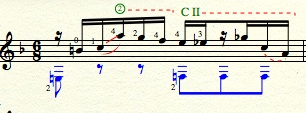

| During the past two years, the International Guitar Research Archive (IGRA) at Cal State Northridge (CSUN) has been increasing activity, acquisitions, and usability for scholars. The largest current project - the digitization of all public domain scores in the Vahdah-Olcott Bickford Collection - is almost complete. IGRA has decided to make public the first group of 1145 high quality photographs of scores in PDF format. As opposed to other repositories of PDFs for guitar music, the IGRA Scores collection contains only full colour scans and is fully searchable. In the coming months, the entire collection that falls in the public domain will be made available to the public. In addition to a large number of scores from the 19th and early 20th century in Europe, this collection also highlights the history of classical guitar in North America with rare scores published throughout the 1800s in the United States You can browse the collection here. Please bookmark it for further reference. |

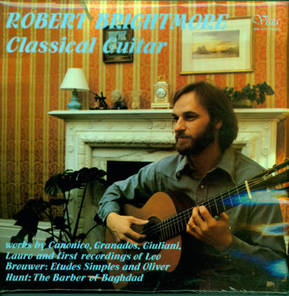

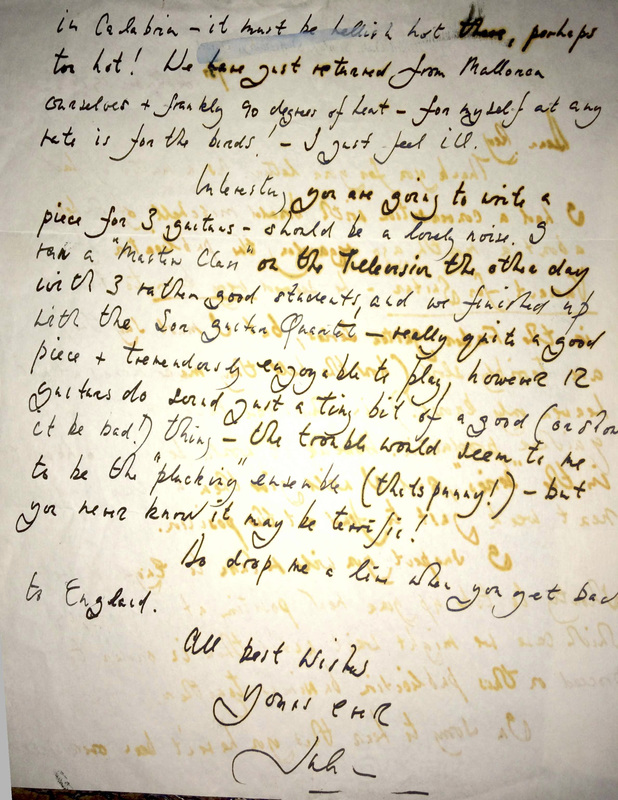

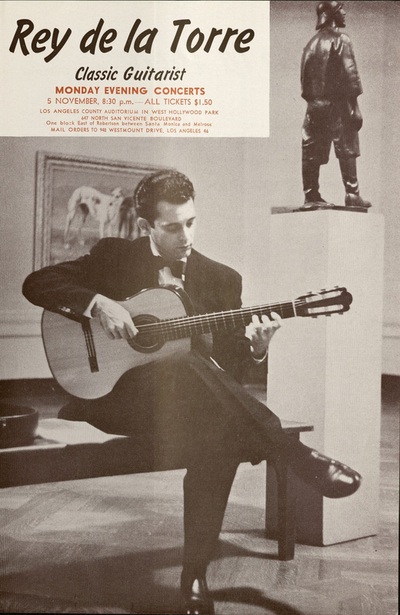

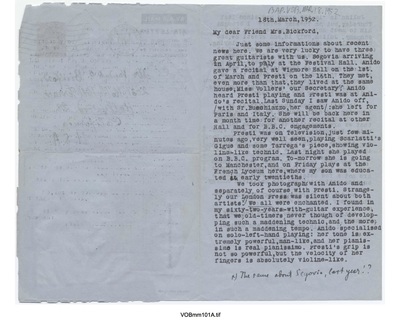

| This addition to the Archives' online functionality compliments our digital collection of the Vahdah-Olcott Bickford Correspondence. The collection of over 500 letters provides fascinating insight into the history of the classical guitar in the early part of the 20th century. We have now added full text searchability to all correspondence, in addition to high quality color scans of the letters. Additionally, researchers and guitar enthusiasts will be excited to browse the IGRA Discography. The discography features thousands of guitar LPs, most of which have downloadable full color scans of the front cover and back/cover liner notes. We are in the process of making all the liner notes completely text searchable, which will also facilitate research into the instrument's history. Researchers interested in listening to recordings should contact IGRA directly |

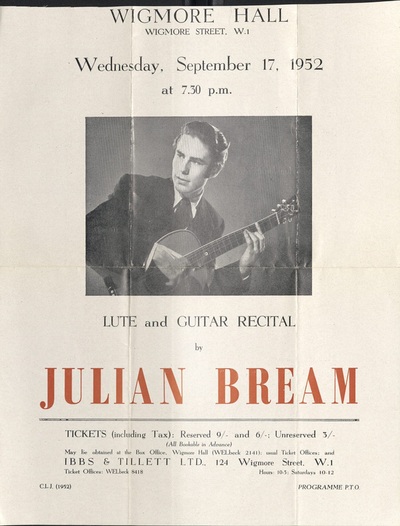

| The archive has been acquiring exciting new collections over the past two years. The most noteworthy is the Reginald Smith-Brindle Collection. After working with the Smith-Brindle family during a research project, I became familiar with the vast wealth of material amongst his personal papers. Working with the family, all documents have been moved to Los Angeles for preservation and they currently are being processed. The collection features manuscripts for virtually all of his works catalog, unpublished works, and some works presumed lost. His unfinished autobiography is amongst the documents, as well as his correspondence with major figures, including John Williams, Julian Bream, Andres Segovia, Luciano Berio and Luigi Dallapiccola. Scholars who wish to view the materials should contact the Head of Special Collections for information on processing time and availability. If you have any specific questions about the contents of the collection, I have several pages of notes and can let you know if something you are looking for is there. Please contact me using the contact form. |

I am very excited by the developments in the archive, and the development of our partnership with the International Guitar Research Centre at the University of Surrey. We welcome all guitarists and scholars to participate in the history of our instrument.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed